Vince Lombardi Trophy Centerpieces “City of Silver and Gold: From Tiffany to Cartier” Exhibit at Newark Museum

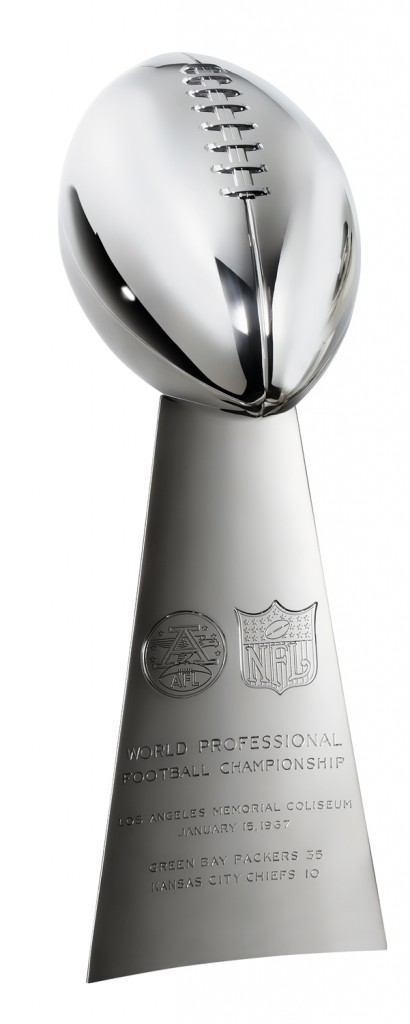

Packers 1967 National Football League Championship Trophy (The First Vince Lombardi Trophy) Tiffany & Co., Newark, New Jersey Silver, 1967 Lent by the Green Bay Packers, Inc.

Though next month will mark the first time New Jersey has ever hosted the Super Bowl, the state has always played a key role in football’s most iconic game. Every year, when the winning team celebrates amid confetti and champagne, the trophy they hoist is a two-foot, seven-pound piece of sterling silver that was designed nearly 50 years ago in New Jersey’s largest city.

Tiffany & Co. crafted the first statuette in the late 1960s at the silver factory it used to operate in Newark, a city that was once considered one of the jewelry capitals of the U.S.

“The trophy is kind of a symbol of what the city used to do,” says Ulysses Grant Dietz, curator of decorative arts at the Newark Museum.

And now it’s making a homecoming. The original trophy — the same one presented to the Green Bay Packers when they beat the Kansas City Chiefs in Super Bowl I on Jan. 15, 1967 — will be on display at the museum on Washington Street in Newark beginning tomorrow.

It’s the centerpiece of a new exhibit called “City of Silver and Gold: From Tiffany to Cartier,” which showcases Newark’s past life as a landmark of the precious metal industry. It runs through March 30.

Dietz says he expects troves of football fans to visit the museum to catch a glimpse of the trophy as New Jersey prepares to host Super Bowl XLVIII at MetLife Stadium in East Rutherford on Feb. 2. But his hope is they won’t stop there.

Mesh purse and belt hook in the Egyptian style Sloan & Co., Newark, 1896-1910 Gold, enamel, turquoise Purchase 1996 Friends of the Decorative Arts 96.21

“My simple fantasy is: You get someone to come look at the trophy and then look around while waiting to get their picture taken and say, ‘Oh, all this stuff was made here, too. Gee, I didn’t know anything about Newark,’” Dietz explains.

The exhibit will feature 115 objects— jewelry, lamps, tea sets, coffee sets, tin trays, and even a horse racing trophy from 1904 — all of them made in Newark at the city’s manufacturing height.

Small jewelry shops began popping up in the Essex County city in the early 1800s. By the time of the Civil War, Newark was an industrial center. Tiffany opened its silver factory there in the 1890s.

By the 1920s, more than 140 jewelry manufacturers called the city home, and Dietz said 90 percent of the gold in America came out of Newark. While New York was the center for expensive, glamour jewelry — diamond broaches for millionaires — Newark was the center of fine gold and silver jewelry, such as wedding bands, kitchenware, or cufflinks.

“People forget that no city starts out poor,” Dietz says. “Newark was an incredibly rich, productive city in its day. It was a real powerhouse.”

The city’s jewelry boom started to fade with the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Dietz explains, but Tiffany remained there for decades.

In 1966, then-NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle had lunch with Oscar Riedner, the company’s vice president, at a swank New York hotel to discuss designing a trophy for the first-ever championship game between the NFL and old AFL. According to legend, Reidner sketched the idea on a paper napkin.

“Most trophies (at the time) were made out of fold-plated metal and plastic,” Dietz says. “This was a real departure in the world of sports. It was kind of a historic moment.”

Those who visit the museum will find that the original trophy — on loan from the Packers — was inscribed with a different name for the event: the “World Professional Football Championship.” The phrase “Super Bowl” didn’t become official until a few years later.

The statue itself was renamed the Vince Lombardi Trophy in 1970, the year the Green Bay coach died. Lombardi, a former coach at St. Cecilia High School in Englewood, led the Packers to victory in each of the first two Super Bowls.

In the 47 years the Super Bowl has been played, there’s been a new trophy for every champion. All of them have been manufactured in New Jersey — first at Tiffany’s Newark plant and then at a new location in Parsippany after the company moved the factory a few decades ago. And while 18 different teams have had their names etched on the side, the trophy’s design has never changed.

Spectacle case, 1908 Bernard M. Shanley, Jr. Company Gold and ruby, 1 ¼ x 1 5/8 x 4 ¾ in. Gift of Mrs. William L. Dempsey, 1980 80.42A,B

It’s a design that Dietz says is worthy the museum space it now occupies: a shining silver statuette with a regulation-size football perched, slightly tilted, on top of a sleek pedestal. That, he says, makes it stand out from other iconic sports trophies, such as hockey’s Stanley Cup.

“The trophy is a work of art,” Dietz explains. “It doesn’t really get talked about that way. Most people don’t think of what it’s meant to symbolize.

“But I think it’s a fascinating piece. It’s kind of designed to embody the sense of flight that a football has. It shouldn’t really be called a football. The main purpose of a football is to move through the air fast. The trophy really brings that out.”

The Newark Museum is open Wednesday through Sunday, from noon until 5 p.m. For more information, visit the Museum’s website at www.newarkmuseum.org.