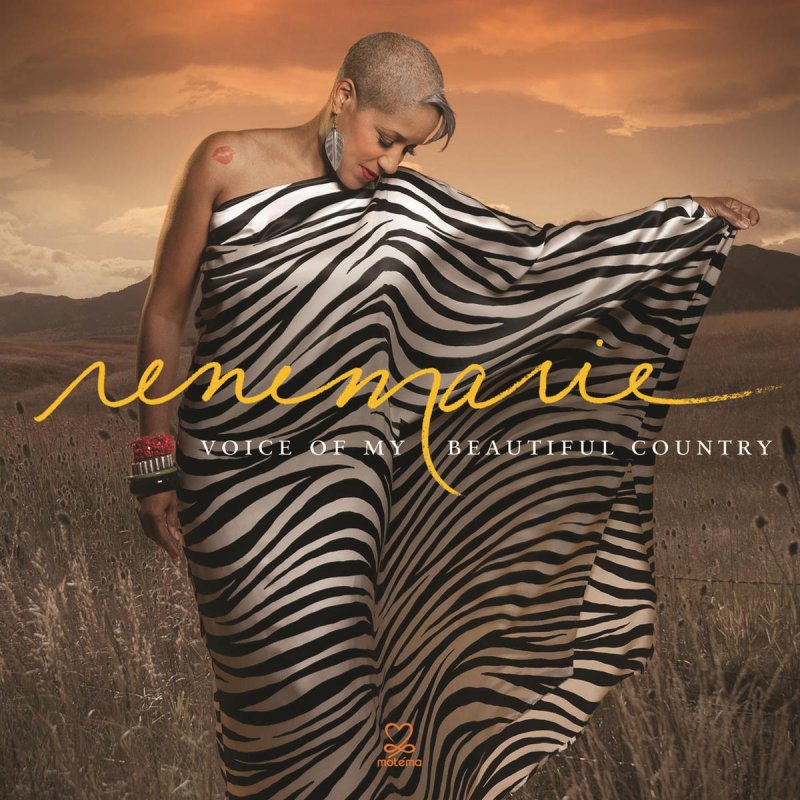

René Marie, World-Class Jazz Singer

The first thing you notice about René Marie is her hair. It’s buzzed almost to the skin, save for a long white lock falling over her forehead. Then, you notice her voice.

Marie is a jazz singer, but hardly a traditional one. She’s as likely to cover Motown, country or Jefferson Airplane’s ‘White Rabbit’ as she is a Tin Pan Alley standard. She’s as likely to write a humorous, defiant anthem about a demanding night-club owner as she is a love song. And she sings all of it in a strong, flexible voice that’s hard to ignore.

Bucking tradition is nothing new for Marie. She didn’t release her first album until she was 42. As a Jehova’s Witness, she was long discouraged from singing in public. But in the mid-1990s, her son encouraged her to perform. Soon, her husband of 23 years gave her an ultimatum: stop singing or leave home. Marie chose the latter.

Now, she’s promoting her eighth album, Black Lace Freudian Slip. She will perform Saturday at the Appel Farm Arts & Music Center in Elmer--it's also worth noting that Jersey Arts members get two for one tickets to this event. Jersey Arts’ Brent Johnson spoke with Marie over the phone about her new music, composing while she drives, why she chose her hairstyle and more.

Jersey Arts: I’ve read that you don’t like being called a jazz singer. Why is that?

René Marie: Because I just sing. And there’s all different genres of music that influence me when I compose. I think if I am a jazz singer, it’s by default. That just happened to be the [record] label that was interested in me first. I think a different genre of music — country & western, R&B — I would have gone that direction. So it wasn’t that I set out to be a jazz singer. It just so happened that that was the first thing that came my way. It was my first marriage proposal, so to speak. And you don’t turn down your first one, because you never know if you’re going to get another change. But my original stuff, when I compose, most of it is not jazz.

JA: When did you start composing?

RM: I wrote my first song when I was 15. It was about some boy.

JA: Isn’t everyone’s first song about some boy?

RM: [laughs] Yeah, thank goodness for that. So yeah, I wrote my first song, and my group, we performed it — a little R&B group. I ended up marrying the guy, and we stayed married for 20-something years.

JA: Do you remember the title of the song?

RM: Ummm, no. [laughs]

CV: I know you didn’t sing for a long time. So when did you start composing again?

RM: After I got married, I continued to play the piano and compose. As a matter of fact, I didn’t sing publicly, but I wrote a love song for my husband. The name of that was ‘Hurry Sundown.’ I had played it for him years before [I recorded it], but he didn’t think much of it at the time. [laughs]

JA: When you write, do you sit down and make a job of it? Or do songs come to you while you’re shopping at the supermarket?

RM: They come to me while I’m shopping at the supermarket, or while I’m driving.

JA: Do you carry a tape recorder with you, or do you try to keep it in your head until you get home?

RM: Now, you can put it in your phone. So I just turn on the recorder and sing away. Before this technology, I would pull off to the side of the road and write it down, and I would sing the melody over and over until I got it. A lot of the time, the melody doesn’t leave me. It stays with me.

That’s why I don’t turn the radio on in the car. I don’t listen to music in the car or at home. Because I always want to keep the lines open.

Anything at all can inspire me, in terms of melody. It can be a car horn, the rhythm of the drier.

JA: So what in the world does the title ‘Black Lace Freudian Slip’ mean?

RM: I really don’t know, and I’ve tried many times to explain it. Every explanation falls short. Sometimes, I cannot explain right in the moment why I did something. But I don’t let that stop me from doing it.

That term ‘Black Lace Freudian Slip’ had been on my mind for a long time. I thought, ‘I like that phrase. I don’t know what I’m going to do with it. Am I going to write a song about it? What? Is it going to be a play? I don’t know.’ I just held on to it.

And these lyrics that I had written some time ago, they didn’t have a home song. They had nowhere to go. I realized I could take those lyrics and meld it with the title ‘Black Lace Freudian Slip’ and come up with a song. And that’s what I did.

JA: I’ve heard a lot of musicians talking lately about how hard it is to make money playing original music these days. Do you find that true in the jazz world, too?

RM: I don’t think in terms of, ‘I’ve got to make a living at this.’ My approach is different than most probably. My goal is to be true to myself — to really believe I have something to say musically. Can I say I don’t worry about it?

It’s way down on the list of priorities for me. You know that phrase, ‘If you build it, they will come’? If you play it, they will come. I do believe there are people out there just dying to hear something different. They’re dying to hear it. But they’ll never hear it if we don’t have the guts to play it.

And it’s just ridiculous to me that there’s this rule that you’ve got to play the standards first before you branch out. It’s a form of tyranny, I think. It keeps a lot of musicians from expressing their creativity. They’re afraid. I can’t say that I blame them. It is scary to put your stuff out there. But oh my God, I would rather at the end of my life to say I’m glad I did than to say I wish I had.

JA: There’s a song on the new record, ‘This Is For Joe,’ about someone asking you to play more standards, right?

RM: Yeah, it was a club owner. We were working on the songs on our last project for [record label] MaxJazz, and he said that to me: ‘Your songs are turning my stomach. You’re an embarrassment to jazz. Look around these walls — there are pictures of famous singers. They didn’t get there by performing their own songs.’ I think what he wanted me to do was cower me into doing the standards. But what ended up happening was just the opposite.

I didn’t dismiss what he told me. But it occurred to me was: Every standard at some point was a brand new song. So why should I limit my creativity doing what other people have done? I’m not gonna do that.

JA: Another song on the album, ‘Deep In The Mountains,’ was written by your son, Michael Croan. Is there extra pressure on a mother singing a song by her son?

RM: Oh my God, it was the most natural thing. I remember when he first sang that song to me — it must have been eight years ago at least — it was just a capella. I got chills. I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is the best song. I’m so jealous.’ [laughs]

JA: You’ve been singing professionally now for more than a decade. And all you hear about is how the music industry is changing and hurting. Is it easier being an artist now or when you started out?

RM: I don’t pay attention to that. I don’t pay attention to all the hype and what’s said in the papers and the media. Obviously, there are jazz clubs closing because of the economy. But there’s also been some obstacle or some difficulty with musicians doing their own stuff in the artistic field.

Again, I just try to be true to myself. Because I spent so many years not speaking my truth. When I finally divorced my husband, left that religion and started on my own path, I just made a promise to myself that I am going to be true. I am going to say what I’m thinking.

JA: Another thing that’s interesting to me is your hairstyle. How did that come about?

RM: So I was one of Jehova’s Witnesses for 24 years. And when I first started singing, I was still a Witness. I started cutting my hair shorter and shorter. It was like an afro to begin with, maybe three or four inches long. I just really liked the shorter hairstyle. But my husband didn’t like it.

When you’re a Witness, you’re supposed to be subservient to your husband. So after the divorce and after I left the Witnesses, I gradually started cutting it. It was like a huge sign of rebellion. Then, one day, I kept seeing pictures of women with their heads completely shaved. I thought, ‘I wanna do that.’ And I realized: It’s just hair. It will grow back. So one day, I took some clippers and went snip, snip, snip. But I left the bangs because I’ve always been told I have a high forehead. [laughs] I really, really like it. I loved the way I felt with no hair on my head.

It’s extremely liberating. It’s very empowering. Of all the things that women have, they spend a lot of time on their hair, thinking it’s our hair that speaks for us in such a way. But if the hair is not there, then you have to learn to speak for yourself in another way.

JA: With Jehova’s Witnesses, is it simply that singing is frowned upon?

RM: It used to be. Of course, Prince is a Witness now. And Michael Jackson was a Witness. Obviously, they’re not going to frown upon them. They’re high-profile, high-income Witnesses. But in the congregation I was in, I was singing, but it was frowned upon by the elders in the congregation. Some elders and their wives came to hear me. Others would frown upon it and say, ‘You’re being part of the world, you’re exposing yourself to difficult circumstances and fleshly desires.’ Of course, that’s true wherever you go. But they tried to make it seem like it was especially prevalent in clubs.

They did try to get me to stop. But they couldn’t pull out any scriptures to do so, so I just kept right on. The real test came when my ex-husband gave me the ultimatum and said, ‘You either stop singing, or you get out of this house.’ So I chose to leave instead of stopping signing — or instead of living with someone who would issue me an ultimatum.

JA: So what’s next for you?

RM: My project is a long-term one. It’s trying to finish composing the songs that are piling up on my desk. A lot of the songs on Black Lace Freudian Slip were a result of that project — of me just saying, ‘Look. This is getting ridiculous. We’re not going to do any projects with any other people. We’re just going to do René Marie songs. Let’s get those done.’ So I don’t have anything else I’m working on, other than getting another 12, 13 songs completed to put on another CD.

Marie performs Saturday at the Appel Farm Arts & Music Center in Elmer--and, as mentioned above, Jersey Arts members get two for one tickets to this event!