LIFE as We Knew It: : “LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photographs" at Princeton University Art Museum

In a hard-to-fathom turn of events, the world we live in has become a virtual one. Just a few weeks back, I visited the Princeton University Art Museum and saw “LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photographs,” the exhibition that had opened on February 22. And, though I had no way of knowing it then, I got there just in the nick of time. That following week, things started to dramatically change. In addition to most museums closing, my day-job workplace shut its doors to all-but-essential staff (which apparently, I am not) and the adjustment to days filled with news-watching and fretting about food began in earnest.

For me, a great way to step away from everyday life and into a different world for a while is to go to a museum, but doing that now, without the in-person experience component, is tricky. From my observations, though, a great many cultural institutions have resourcefully risen to the challenge of providing remote access to their exhibitions and collections. And the Princeton University Art Museum is an institution that is doing that particularly well.

The primary reason for my trek to Princeton that day, aside from a sunny Saturday drive and a lunch date with one of my favorite people, was to see the museum for the first time and check out the Life Magazine exhibition.

Unknown photographer, “Life photo editor Natalie Kosek reviews photographs,” 1946. Gelatin silver print. LIFE Picture Collection.

I am a sucker for photography exhibitions, and this one looked especially interesting from the information and images on the website. And, I asked myself, how could I not enjoy learning more about the magazine that had graced so many coffee tables and newsstands during my childhood and teenage years?

I was also fascinated by the overall idea on which the exhibition was built – that, during its glory days, LIFE magazine told stories in an original, image-heavy fashion, using photographs to depict a particular representation of American life. As the book published in conjunction with the exhibition states, “the magazine pioneered the form of the photo-essay – and both revealed and mythologized the United States.”

We all know the adage, “a picture is worth a thousand words” and the almost indisputable premise – that a single image can communicate as much depth and clarity as a lengthy written description.

In this exhibition, though, the curators – Katherine A. Bussard (Peter C. Bunnell Curator of Photography at the Princeton University Art Museum), Kristen Gresh (Estrellita and Yousuf Karsh senior curator of photographs at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), and Alissa Shapiro (a Ph.D. candidate at Northwestern University) – take the concept to another level, saying that images not only have the power to tell stories, but the effect of the images can be altered by the way they are presented.

W. Eugene Smith, American, 1918–1978, “Nurse Midwife Maude Callen Delivers a Baby, Pineville, South Carolina,” 1951. Gelatin silver print. Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, Fowler McCormick, Class of 1921, Fund. © 1951 The Picture Collection Inc. All rights reserved.

So, rather than focus only on iconic photos from the magazine’s 36-year run and the photographers who took the pictures, the exhibition explores the far-reaching impact on photography that LIFE’s contributors and staff had through the magazine’s signature style of visual storytelling.

Bussard explained how the idea came about. “In the past several years, I noticed that a number of colleagues had organized exhibitions around photographers who contributed to LIFE magazine,” she said, “but those were monographs, about the legend of a particular photographer.”

“None talked about what the magazine did,” Bussard said.

“The exhibition is not thematic or chronological. The photographers are not the story.”

Then what is the story?

Excerpts from the website explain, “The exhibition examines how the magazine’s use of images fundamentally shaped the modern idea of photography in the United States. The exhibition presents an array of materials, including caption files, contact sheets, and shooting scripts, that shed new light on the collaborative process behind many now-iconic images and photo-essays.”

Alfred Eisenstaedt, American, born Germany, 1898– 1995, “Detail of contact sheet, Times Square, New York City,” August 1945. Gelatin silver print. LIFE Picture Collection. © 1945 The Picture Collection Inc. All rights reserved.

Bussard said that putting together the exhibition was an equal-parts collaboration among the three curators, with each contributing resources from individual research and past projects.

“It’s been a wonderful example of three people coming at something,” Bussard said, “and helping one another to think differently.”

Working collaboratively on the object checklist, for example, was a great experience. “It made each of us think differently, reframe things, and take more risks,” she said. “I really valued the push and pull of that.”

LIFE concluded its weekly run in 1972, and one might question how insights from this exhibition have relevance to the modern world. It’s almost trite to point out how things have changed in the nearly-50 years. And certainly, when it comes to technological advances since the ‘70s, you could say that everything is different.

But the basic ideas – that an image speaks volumes and that how it is presented can be as significant as the image itself – is as relevant now as it was in the heyday of picture magazines.

Bussard is a professor at Princeton and, before the lockdown, enjoyed bringing students to see the exhibition.

“I had a photo class in, and they spent a lot of time examining the contact sheets,” she said. “It made them think through their own choices – how to frame a shot, which photos to select to convey what you want to say.”

Bussard and I discussed the demise of LIFE and talked about what, if anything, has replaced it.

The why part is simple to explain, she told me. Production costs were rising, and television’s dominance was causing valuable advertising revenue to be reallocated. More was going out, less was coming in.

But the enormous cultural changes of the ‘60s and ‘70s was another, less-apparent factor in the equation.

“What was happening in America then no longer matched the homogenized post-war life that LIFE portrayed,” she said.

The answer to the second part of that question – what is a comparable today? – is more complicated.

“I asked my students where they get their news,” Bussard said, “and a number told me that they listen to podcasts, which don’t have images.”

But when she asked where they see images, they noted that social media platforms, like Instagram, are primarily driven by moving and still images.

“The most amazing thing to me,” she said, “is that we’ve landed in an image-driven world where we are inviting people to return to a time when that was a bold move.”

But Bussard believes that the forces at work now when digital images are universally accessible, are not that different.

“The process that gets images into a slideshow is still about making key choices.”

“What we hope to do with this exhibition,” she said, “is help people think more deeply and critically about the images they are seeing at this very moment.”

Robert Capa, Hungarian, 1913–1954, “Normandy Invasion on D-Day, Soldier Advancing through Surf,” 1944. Gelatin silver print. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Howard Greenberg Collection—Museum purchase with funds donated by the Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Charitable Trust. Robert Capa © International Center of Photography. Photograph Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The Princeton University Art Museum is currently closed. You can follow the museum on Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to view digital versions of works from the special exhibitions and the museum’s rich permanent collection, and keep up to date on museum news during the closure.

“LIFE Magazine and the Power of Photography” is on view through June 21, 2020. The museum website provides many options for getting a closer look at objects and information from the exhibition. The other special exhibition, “Cezanne: The Rock and Quarry Paintings,” is on view at the museum through June 14, 2020. Information about this exhibition can be found here.

Fully illustrated catalogs for both exhibitions can be ordered from the Museum Store.

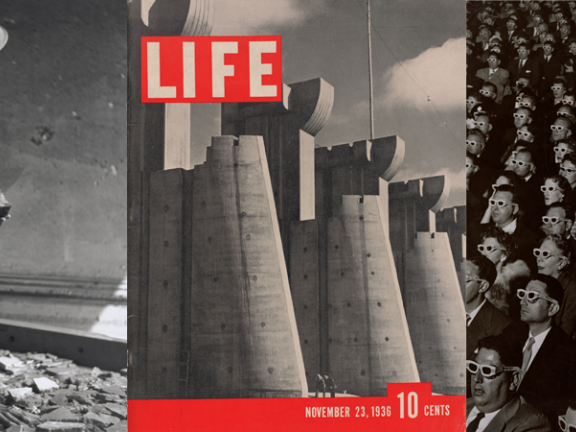

Cover image photos:

Gordon Parks, American, 1912–2006, "Gang Member with Brick, Harlem, New York," 1948. Gelatin silver print. Princeton University Art Museum. Museum purchase, Hugh Leander Adams, Mary Trumbull Adams, and Hugh Trumbull Adams Princeton Art Fund. © The Gordon Parks Foundation

Margaret Bourke-White, American, 1904–1971, "Cover of LIFE Magazine," November 23, 1936. LIFE Picture Collection. ©1936 The Picture Collection Inc. All rights reserved

J. R. Eyerman, American, 1906–1985, "Audience watches movie wearing 3-D spectacles," 1952. Gelatin silver print. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, The Howard Greenberg Collection—Museum purchase with funds donated by the Phillip Leonian and Edith Rosenbaum Leonian Charitable Trust. © 1952 The Picture Collection Inc. All rights reserved. Photograph Courtesy Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.