Joyce Kozloff's debut solo exhibition in NJ - "Cradles to Conquests" - on view at Rowan University Art Gallery

The first piece of art Joyce Kozloff remembers making was a set of paintings she created more than six decades ago — as a young student in the small Somerset County borough of Manville. “When I was in elementary school, I did a series of watercolors showing clouds at different times of the day,” Kozloff recalls. “My teacher liked it. And I put it up on the walls.”

It was the beginning of a beautiful career. In the 1970s, Kozloff became one of the prominent figures in feminist art and one of the founders of the Pattern and Decoration movement. Her art has been exhibited across the globe.

“She is one of the artists out there who has a reputation,” says Mary Salvante, curator of the Rowan University Art Gallery.

Now, Rowan is helping showcase Kozloff’s work in her home state. The Glassboro school is hosting the artist’s first solo exhibit in New Jersey, called “Cradles to Conquests: Mapping American Military History.”

The exhibit, which runs through March 15, is a far cry from watercolor clouds. The pieces on display use maps, collages, and cartography to examine the role the U.S. military plays in the world — and also to explore how images of war are formulated in the minds of boys early in their lives.

Jersey Arts’ Brent Johnson spoke with Kozloff about growing up in New Jersey, how she started mining themes of warfare, and what’s next in her career.

Jersey Arts: So you’re from Somerset County.

Joyce Kozloff: We lived in Manville until I was 12, then we moved to Bridgewater Township outside of Bound Brook. I went to Bound Brook High School. My mother still lives there. She’s 98. She came to the opening (of this show).

JA: Did you obtain an interest in art from your family?

JK: There was a lot of music in my family. My mother played the piano. But visual art was not a big thing.

JA: Did your love of art develop out of the music at all?

JK: It didn’t come from the music. Like a lot of artists I know, I was the school artist in elementary school. I was encouraged to do art. After a while, as I became a teenager, I liked it more and more. Somehow, I got this crazy idea in my head to become an artist. I went to art school at Carnegie Mellon — which was called the Carnegie Institute of Technology at the time.

JA: Did New Jersey help inspire your art?

JK: Not too much. In a way, art was a form of rebellion for me — breaking away from certain kinds of more conventional upbringing. I didn’t know very much about art. We didn’t go to museums very often. But one summer when I was in high school, I commuted to the Art Students League of New York to do drawings. I think it was between my junior and senior year. I was really eager to really learn more about how to make art. I also wanted to be in a more urban environment.

JA: What did your mother think of the new exhibit when she saw it?

JK: Oh, she’s very proud of me. She always comes to my shows. Until my father died, the two of them always came. They’d travel long distances to be there.

JA: This time, she doesn’t have to, since this is your first solo show in New Jersey.

JK: I don’t know why it didn’t happen sooner. I didn’t seek it out. I didn’t think about it, actually. I have been in group shows in New Jersey over the years. I’m in two of them now actually — in Summit and Montclair.

JA: What is the idea behind the Rowan exhibit?

JK: It focuses on a certain part of my work. I didn’t realize I had done so much on the theme of war to make a full show of it. The idea actually came from (museum curator) Mary Salvante, and it was a good idea. It was work she chose from different bodies of work of mine over a 10-year period. I had been working with mapping for more than 20 years — using it in different directions in terms of aesthetic and content. These pieces specifically had to do with war.

JA: What do you think the pieces say about war?

JK: I’ve been a peace activist in my life. I use the maps as a structure to weave different kinds of content into. The first piece I did about war is a globe — called "Targets." I began it in 1999 and finished it in 2000. I was thinking about aerial warfare — the horror of aerial warfare. The victims are largely not combatant. This has escalated in my life, compared to the conventional warfare among soldiers in the past. I wanted to dramatize the experience of aerial warfare. It took me a couple of years to conceptualize that piece. An artist has to tell his or her ideas through his or her own visual language. I’m not like a realist painter that would paint scenes of battles. I have to find a form to tell this story with my own visual vocabulary.

I did a body of work in the ’90s based on nautical charts. But a friend of mine whose father had been in Air Force said, ‘You should look at aeronautical charts.’ I was unaware of these things. So I started ordering them from NOAA (the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). They have aeronautical charts — tactical pilot charts of every place on the planet. Pilots need them to navigate. You can order them for very little money. They are large and they are beautiful. I first ordered them during the wars in Bosnia and Serbia. I ordered maps of those areas. Then, I ordered maps of other areas that were sites of current conflict at the time. I incurred a lot of those maps. They were all over my studio. I didn’t know how I’d use them in my own work.

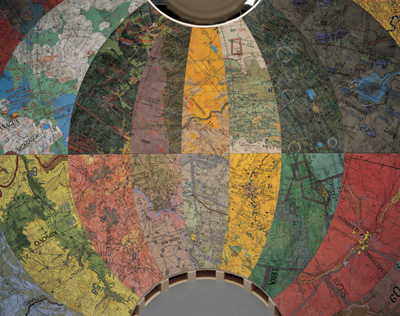

Then, in 1999, I went to the American Academy in Rome for a year-long fellowship—which was wonderful. I had been applying for it all my life. I had a big studio and a lot of time. I brought the charts with me. They were all over the studio. Before that, I had been making little table-top globes. I wanted to expand the globes. I was inspired by the dome of the Pantheon in Rome — the light comes in through dome above and other dome-like structures. Suddenly, I imagined a very large globe.

I was a little scared. I’m not a sculptor. But I found these carpenters near where I was living. We worked it out together. They built it. I painted aerial maps inside of it. Each map is a place the U.S. bombed from 1945, the end of World War II, to 2000, when the piece was made. Some of them were minor skirmishes. Some of them were big wars. There were 24 places inside of the globe — canvas glued onto wood. Each one of them is based on one of those tactical pilot charts. I painted them all in different colors. I didn’t want it to look like one continuous world. What they had in common was the trauma of being bombed.

You can enter the globe with two or four people. And when you talk, there is a very pronounced echo. The shape of the globe amplified the sound. I did not anticipate it. But it really adds to the experience.

That was the beginning. And that’s a long answer to a short question.

JA: What happened after that?

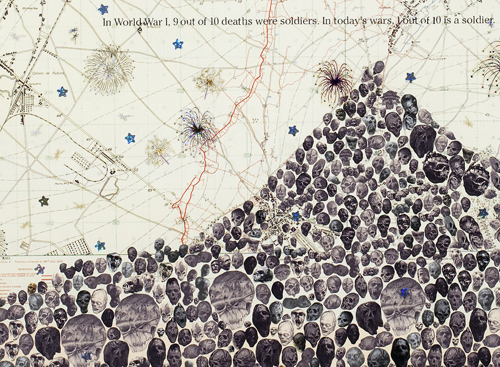

JK: Then I was off and rolling with this theme of war and warfare. One body of work was based on World War I trench maps. I was in London, and I went to the Imperial War Museum. You can actually go into a trench there. I went into the gift shop, and they had a whole wall of these trench maps. I bought a bunch of them. That was the basis for another body of work — called Map Of Destiny.

JA: Do you anticipate making any other war-themed pieces?

JK: I think I’m kind of finished with it. I feel like I’m moving away from it. It’s a heavy thing to carry with you for 10 years.

JA: What other kinds of pieces are in this exhibit?

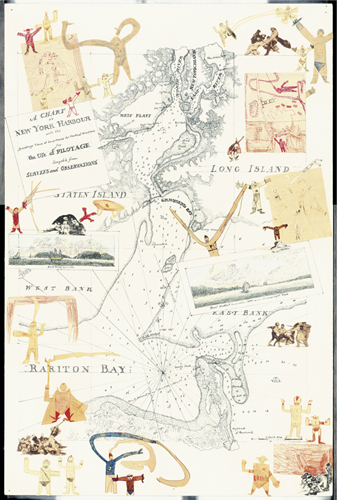

JK: Another body of work is called Boys Art. That’s a body of work I really, really love. I did that in 2001. It included drawings I made from maps of battles all over the world. And I included some of my son’s drawings featuring battles of super heroes. He’s now 44. When he was pre-adolescent, he did these drawings that little boys do. They’re great, so I kept them.

It was pre-Photoshop, so I took them to my local copy shop. They had them Xeroxed down until they were very small, so I incorporated them into the maps. It made me think of the kind of art boys make versus the kind of art that girls make growing up.

JA: You are known mostly for being at the forefront of the feminist and Pattern And Decoration movement in art. Do you feel your mapping work gets overlooked in your output?

JK: The work I’m doing now is an attempt to bring patterning and mapping together. I’m excited about it. It’s an interesting challenge. It is moving away from themes like warfare. I am trying to celebrate life now.

"Cradles to Conquests: Mapping American Military History" is on exhibit at Rowan University Art Gallery until March 15.

Editor's Note: Our friends at State of the Arts also did a piece on this exhibit and Ms. Kozloff. You can check it out at http://bit.ly/1nBpi2e.