Hunterdon Art Museum: Three New Exhibits

Just off Main Street in the western New Jersey town of Clinton sits a gorgeous structure: a 19th century stone mill on the banks of the Raritan River.Step inside, and you’ll find something just as striking: walls lined with paintings, pictures and sculptures by artists from around the nation.

The old mill is home to the Hunterdon Art Museum, one of a handful of places tucked away in the Garden State that prove you don’t have to cross into New York or Philadelphia to experience fine art. You can visit art museums in Princeton, New Brunswick, Trenton, Morristown — and yes, a riverfront, rock-covered building on the national registry of historic places, just off Route 78 in rural Hunterdon County.

“It’s a place we always want more people to know about,” says Jonathan Greene, the Hunterdon Art Museum’s director of exhibitions. “Every person who comes, they love the building and they love the area.”

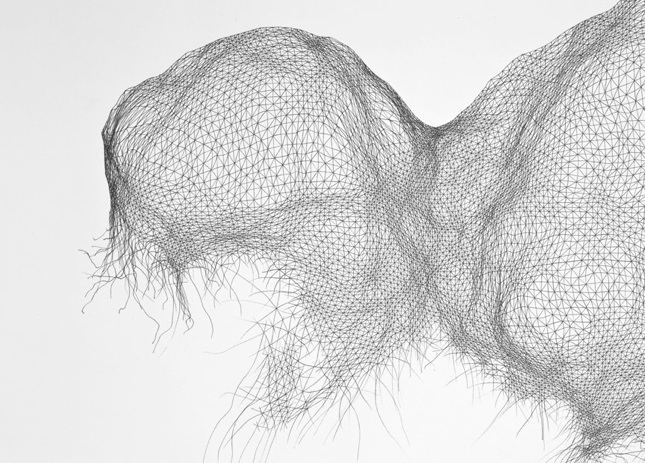

The art is pretty interesting, too. The museum holds about 12 shows a year, Greene says. — with three exhibits currently on display. “Fragmented” consists of intricate, interweaving drawings by four artists: Astrid Bowlby of Philadelphia, Ben Butler of Memphis, Tenn., Sebastian Rug of Germany, and Christopher Skura of New York. “No Longer, No Later” features four colorful, abstract paintings by Brooklyn artist Elizabeth Gilfilen. And “The Clockmaker’s Apprentice” includes 100 cuckoo clocks — all deceivingly made of foam rubber by Nathan Skiles, an Indiana native who received his masters degree in fine arts from Montclair State University.

Greene spoke with Jersey Arts’ Brent Johnson about the museum and its new exhibits.

Jersey Arts: The museum is kind of like a hidden gem in New Jersey, isn’t it?

Jonathan Greene: Yeah. It’s my job to do what I think is engaging and find artists that I think are interesting. I don’t expect everybody to love every show, but for them to love the area and the architecture of the museum is always an important thing. And it’s not just people in New Jersey. We’re equidistant between New York City and Philadelphia. It’s really a great spot to drive to. …For us, it’s a great place for people to spend a half-day. So even if they have to travel an hour, there’s plenty to do. They can go to the Red Mill [another historic spot on the opposite side of the river], they can enjoy the scenery, they can walk the town. There are plenty of restaurants and shops. I think that’s one advantage we have — a lot of people from bigger cities and bigger lives can relax.

JA: What is your relationship to Hunterdon County?

JG: We would like to be a regional hub of art, and you always want the whole county to be involved. But as with any place, it’s just dependent on what people think. And your job is to really try to get them there once and to take it from there. I think we’re certainly a valuable resource in the area. There’s no other museum of our size too close by.

JA: Can you explain more about the “Fragmented” display? It seems a little abstract.

JG: It’s pieces by four drawers — done with pencil or pen and paper. It deals with the obsession of drawing. Each drawer as they go is making smaller marks to end up in a larger drawing. And all of them, if you look at them closely, it looks like if you would just take one part out, the whole thing would be destroyed. They’re entirely dependent on parts of each other. So the inverse would be: They could become easily fragmented if one piece were removed. Because of their dedication to the process, they piece all these things together that create these larger works that are interconnected. I think it turned out to be a nice show.

Finding themes for group shows, I think I do things differently. I don’t find artists and make a theme from artists I like. I have an idea and then I find artists and work with them as it goes so when people walk in, they see right away the show makes sense.

JA: And Elizabeth Gilfilen’s exhibit?

JG: She’s an abstract painter. I think abstract work for viewers can be difficult. But I think if they react to color, once they engage, it becomes less about trying to figure out what it is. Because they know right away it’s not a boat or a bowl of fruit. They have to find something they like about it. And her way of painting — the technique and kind of curious movements in the middle — I think drives people to engage with it more. …It’s a great balance to the drawing show, which is mostly black-and-white. When I look at the program, I look at how all three exhibitions — how they work together and how viewers can go and transition from one to another. And this one is perfect. While you’re walking around the drawing show, you can kind of see through the door to the small gallery and see this big burst of paint and movement and color.

JA: The third exhibit — by Nathan Skiles — is on the first floor, and the museum describes it as a “treasure hunt.” How so?

JG: There’s a hundred foam-rubber cuckoo clocks. This is one of those things that you have to see to really get it.

One of his goals in making the work that he does is the idea of tricking the viewer and making people dispute the fact that it’s real. I mean, he has all the tools that he uses to make these things on these faux cuckoo clocks. There’s scissors, levels, glue, tape and Band-Aids. Everything that people assume right away when they walk in, they’re like, “Oh, he’s just putting stuff on there” — but it’s not. Everything’s made of foam rubber. No matter how many times we tell people that everything is made of foam rubber, they still ask. But there’s nothing on any of them that’s not made out of foam rubber.

It’s an engaging environment. It’s definitely overwhelming, and that was the point. He took the space into consideration to give a kind of immersive experience and to draw people in.

Art featured in this article:

Ben Butler,Invention #50 (detail). 2010 Ink on paper, 26 x 40 inches Courtesy of the artist and Coleman Burke Gallery

Elizabeth Gilfilen, Cusp, 2012 Oil on canvas, 42 x 40 inches Courtesy of the artist

Nathan Skiles Golem #8, 2011 Cuckoo clock with tools, foam rubber, 13 x 12 x 11 inches Courtesy of the artist