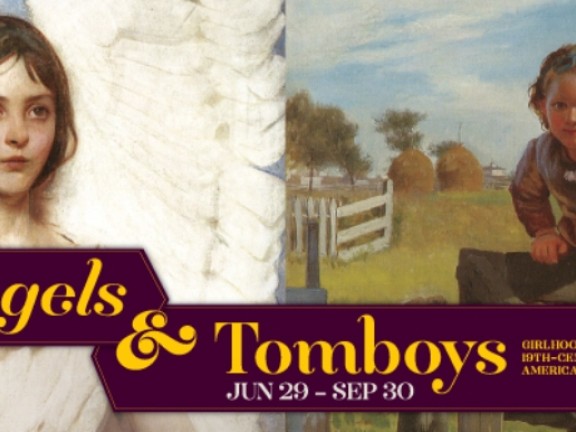

Dream girls: "Angels & Tomboys" at the Newark Museum

“Angels & Tomboys: Girlhood in 19th-Century American Art” isn’t just a new exhibit of paintings and sculptures at the Newark Museum. It’s also a lesson in history. In the late 1800s, as the Civil War ended and women took on new roles, artists began exploring the subject of girlhood in a deeper, more detailed way, explains Holly Pyne Connor, the exhibit’s curator. Whereas girls were once shown mostly as angelic, innocent creatures, they were now being depicted as tomboys interested in hunting, students who could learn as well as boys, and teenagers squirming uncomfortably beneath heavy dresses and corsets.

“There was a new understanding of adolescence,” Connor says. “Talented artists were portraying these new feminine types.” Walk along the walls of “Angels & Tomboys” and you’ll witness this sea change unfold in about 80 pieces by esteemed artists like Cecilia Beaux, Winslow Homer, John Singer Sargent, Seymour Joseph Guy and William Henry Lippincott. “Many of the works are drop-dead gorgeous,” Connor says of the exhibit, which runs through Jan. 6. “If people want to go around and just be inspired by the art, that’s definitely available to them. But I think if they spend some time and read the label copy, they can learn a lot about the lives of women in the 19th century and some of the social events that were changing girlhood.”

The exhibit begins with androgynous toddlers. In the 19th century, Connor explains, parents often dressed young children in similar clothing, regardless of gender — even putting boys in gowns. The kids in Ammi Phillips’ 1832 paintings “Girl in Pink” and “Boy in Red” both wear dresses and short cropped hairstyles. Only if you look closely can you tell their sex: The girl holds a flower, while the boy holds a hammer. More than 150 years later, it’s a theme that continues to resonate every time a little boy dressed in a yellow jumper gets mistaken for a little girl. “Even though we do now tend to use color often to determine which is the boy and the girl, this idea of childhood androgyny is still slightly in evidence today,” Connor says.

Femininity is more obvious in Abbott Handerson Thayer’s “Angel,” the 1887 piece that lends the exhibit half of its title. It’s a portrait of the artist’s 11-year-old daughter Mary — in a white dress and large angel wings. “I think it’s playing upon the myth and reality of girlhood,” Connor says. “On the one hand, the idea that girlhood is angelic, pure, innocent is certainly an important aspect of this period. But also, it’s a unique portrait. And I think the body does have some corporality about it, which really references the idea that girls are fragile, human and vulnerable.” Another theme explored in the exhibit is the child of nature — the idea that “girlhood is a kind of spontaneous and free state,” Connor explains. Many of the paintings depict women against beautiful pastoral backdrops. “At this point in American history, the country was becoming very industrial and urban,” Connor says. “I think audiences were kind of looking back to an earlier period in American life in a nostalgic way.”

Then there was the war that tore the country apart. The Civil War claimed more than 600,000 lives, leaving women to take on different roles and professions, Connor explains. This idea is displayed in the work of Lilly Martin Spencer, a Newark painter whom Connor calls the most important female artist of the mid-19th century. In “The Home of the Red, White and Blue” (1867-68), girls and women dressed in pretty gowns gather in front of a tattered American flag — while the male figure is “marginalized,” shown in shadow, sitting on a chair in the corner of the painting, Connor says. “The narrative here is that it’s the women and the girls who are going to repair the nation,” she explains. This ideal also helped give rise the second part of the exhibit’s title: the tomboy. Maybe the best known example in the 19th century was Jo March — the young heroine in Louisa May Alcott’s novel "Little Women" — who dreamed of becoming a famous author.

Quotes from the novel and other passages relating to girlhood from the period are plastered on the wall above the paintings in the exhibit. “I can’t get over my disappointment in not being a boy,” reads one of Jo's quotes. “I can only stay home and knit like a poky old woman.” “Suddenly there were other role models for young girls,” Connor explains. “The angelic creature was not something a lot of girls felt comfortable emulating.” The two generations clash in Eastman Johnson’s “Flying Kite” (1865). An older woman in plain dress sits in a field, knitting. A younger girl in bright blue and red clothing stands next to her, flying a kite against the sky in a “very bold stance,” Connor says. Still, “Angels & Tomboys” also shows female adolescence being a period of emotional turbulence. In William Merritt Chase’s “Young Girl in Black” (1897-98), the artist’s 13-year-old daughter Cosy is shown posing in her mother’s giant black dress.

“She seems to be neither a girl nor a woman,” Connor explains. “She looks quite uncomfortable. It’s that sense of the awkwardness of teenage years. A lot of women talked about how devastating it was. As young children, they were allowed to run free, they were allowed to play with their brothers. But then, as they started going into puberty, they were put into corsets, their hair was bound, they had floor-length skirts.” In Johnson’s “The Party Dress” (1872), a young girl is being fitted for a lacy gown, but her eyes are shown gazing out the window. “She’s really thinking about the fact that she’ll be leaving home before too long,” Connor says. “Her life is going to be somewhere else.” For many girls, that meant the classroom. Before the late 1880s, it was mostly men who went off to high school and college. But that changed at the end of the century. And not just for white girls. John Rogers’ plaster sculpture “Uncle Ned’s School" (1869) shows a black girl teaching her uncle to read. “It’s the younger generation instructing the older generation,” Connor explains. But while the exhibit may focus on girlhood in Civil War America, Connor stresses that many of the themes are still relevant today. “People tend to have a personal identification or personal memory about what the narrative may be and how it resonates with them,” she says. “It’s not a dead 19th-century topic.”

"Angels & Tomboys: Girlhood in 19th-Century American Art" is on view at the Newark Museum through Jan. 6 before traveling to the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art in Memphis, Tenn. and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Ariz. Suggested admission is $10 for adults and $6 for children, seniors, students and veterans and their families with valid ID.