With Contributions to Theatre, Literature, Visual Arts, and Social Justice, Rhinold Ponder’s Impact Can be Felt Throughout Central New Jersey

In his 62 years, there’s not much Rhinold Ponder hasn’t accomplished.

He’s been an attorney, a writer, an activist and curator; he’s started nonprofits (Art Against Racism) and rescued others (New Brunswick’s Crossroads Theatre, where he served as board president during a time of crisis). He has a plethora of degrees — after studying political science at Princeton University, he went on to get two master’s, one in journalism and the other in African-American history, before completing his juris law degree. Married to one-time Princeton Township Mayor Michele Tuck-Ponder, Rhinold has co-parented two young adults, one of whom recently became on-air journalist for CBS Chicago, and one is still in high school.

Rhinold Ponder

Ever driven, Ponder is also an accomplished fine artist. His current exhibition, Overcoming: Reflections on Struggle, Resilience, and Triumph, is on view at the Arts Council of Princeton through March 5.

Inspired by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “We Shall Overcome” proclamation, these paintings “provoke reflection on the resilience of Black people in their continuing struggle for recognition of their humanity and demand for human rights,” Ponder says in an artist statement.

He admits that he cries while he paints. “Sometimes joylessly. Sometimes painfully. But my emotive response during the creative process always lets me know when my work has a chance of touching someone else.”

Although the exhibition fills a small gallery space, the emotions it stirs ripple beyond the building. In “Maafa: Ghosts of the Atlantic III,” we see a figure under water with shackles on her ankles, a fetus in her belly.

Maafa is a Kiswahili term meaning great disaster or terrible occurrence, referring to the Middle Passage or Transatlantic Slave Trade during which millions of Africans were killed.

Rhinold Ponder, Maafa Ghosts of the Atlantic III, mixed media acrylic, 30in x 40in, 2018.

“In teaching American history, we have ignored the atrocities that have dehumanized people,” says Ponder. “I wanted to rediscover humans lost in such large numbers. This narrative of a chained woman drowning with a child leads me to ask, ‘Did she escape? Is she trying to free her child? Or was she thrown overboard?’”

Throughout the murky waters we see shadowy skulls and ghosts. It’s a beautiful rendering of the sea, until we get up close to see what’s really going on and it becomes painful.

“I try to make the ugly as beautiful as possible to attract you to it and make you stop and think,” says the artist.

Talking about it, tears well up. And the tears came to this writer as well, both viewing the works on her own, and upon hearing Ponder talk about it.

“We know the atrocities that occurred during the beating of people in slavery,” he says, “but we don’t have the visuals. I wanted to show the back of a human being who’d been beaten and whipped.”

Rhinold Ponder, Keloids and Scars II, mixed media on leather, 36" x 24", 2018.

For “Keloids and Scars I” and “Keloids and Scars II,” made on “whipped leather,” he sourced leather coats from resale shops, cut them up, and enlisted Michele, a quilt artist, to piece them together on a stretcher. He hung the canvases from the bough of a tree in his backyard and literally whipped them until keloids and scars formed on the hide. He filled these wounds with red and gold paint. “It was not a fun experience,” he says, trying to hold back more tears. “I wanted to pay attention to my emotions and be fully in the experience. I found a surge of power, and an anger that led to my beating it again and again.”

As a child, Ponder had been spanked “often for the wrong reason, and out of anger.” It made him think about the emotional state of a person who would do this to get someone to obey. “I can’t explain the exhilaration. I didn’t expect it. I don’t consider it a positive.”

In “Hands Up Don’t Shoot,” begun before the murder of George Floyd, Ponder painted panels of police shootings of unarmed Black people “but couldn’t keep up.” What caught his attention were that shots were fired multiple times. “Their targets were dehumanized, and their inflicting of pain heightened their emotional exhilaration.”

Rhinold Ponder, Keloids and Scars IV, mixed media on leather, 36" x 24", 2018.

But there is hope. “Despite the beatings, the terror, there’s been triumph. Black Americans can still lead lives of joy and participate,” he says.

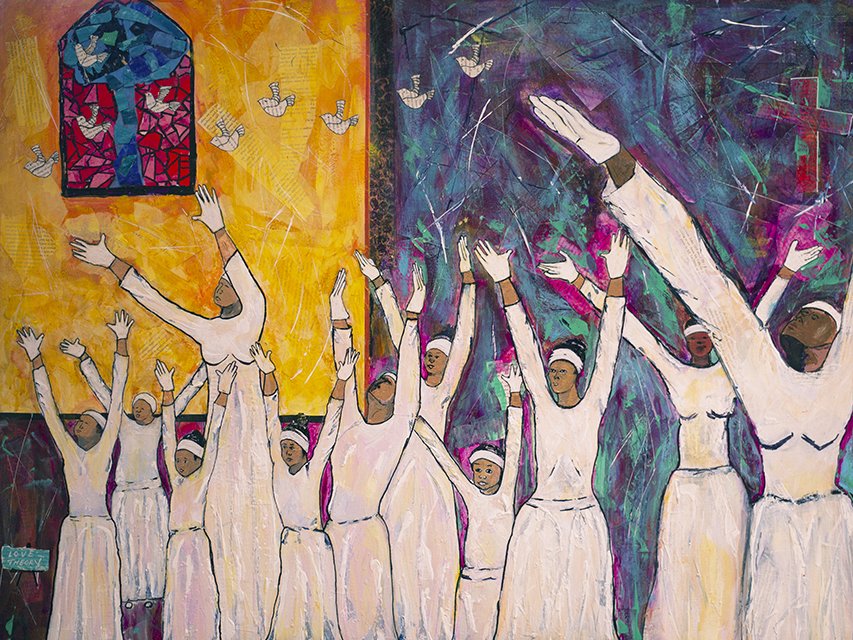

In “Love Theory I,” we see bronze-skinned women and girls in white skirts, white leotards, white headbands, white gloves, holding their arms up to the white doves flying overhead. It was inspired by a praise dance at the First Baptist Church of Princeton. Embedded into the collage are torn-up bits of text from overrun copies of books on African American sermons that Rhinold and Michele published in the 1990s, “Wisdom of the Word: Faith” and “Wisdom of the Word: Love” (Crown).

“I’m not religious, but the church played a large role in my life,” says Ponder, whose father was a pastor. Church attendance was mandatory when he was growing up. “Church was more than a building – it was a call of faith within the community. Sermons contain some of the greatest stories.”

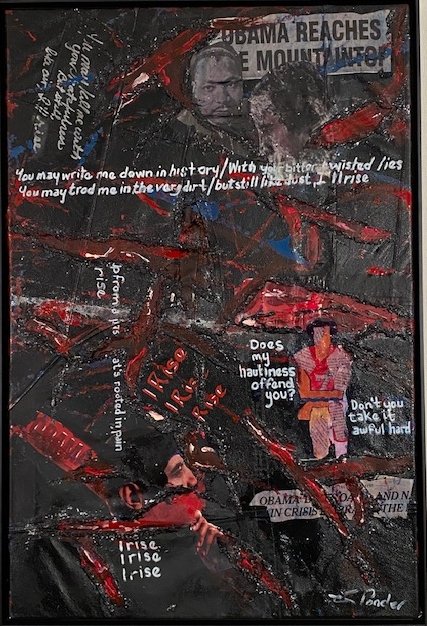

Cut-up words is a continuing motif in his painting, including the lines of Maya Angelou (“I rise I rise I rise”) and headlines from newspapers such as “Obama Reaches the Mountaintop.” In “Abstract Tulsa,” Band-Aids cover over the N word in various headlines about the massacre against African Americans and the government coverup.

“Band-Aids only partially solve the problems of pain; the sore still exists,” says Ponder.

Growing up the eighth of 11 siblings, “my mother raised us on her own and got all her children to go to college” at such esteemed institutions as Princeton, the University of Chicago, the University of Pennsylvania, DePaul, New York University, and Yale. He credits his mother for inspiring him to do what he loves.

Rhinold Ponder, Love Theory I, ", mixed media (acrylic and paper), 30" x 40"

He just happens to love doing lots of things. In addition to writing political essays for The New York Times and others, he’s been writing poetry since high school, when he won a poetry award juried by Gwendolyn Brooks.

As he winds down his law practice, he’s become a founding member of Princeton Makes, where he has studio space to work on larger canvases. And with Judith K. Brodsky, he is co-curating an exhibition for the Arts Council of Princeton, scheduled to open October 20, about a group of overlooked mid- 20th century Black artists working in and around Princeton.

With Overcoming, Ponder himself is unlikely to be overlooked.

Cover photo image includes Tulsa Bandaged (cropped).