Celebrating Native American Heritage Month at the Morris Museum

November is Native American Heritage Month. It started as one day of recognition (the second Saturday of May) more than 100 years ago. It was called American Indian Day and honored the contributions the first Americans made to the United States.

Through the years, many states started celebrating the day in different ways – some replacing Columbus Day with Native American Day. It was President George H. W. Bush who first designated November as “National American Indian Heritage Month” in 1990.

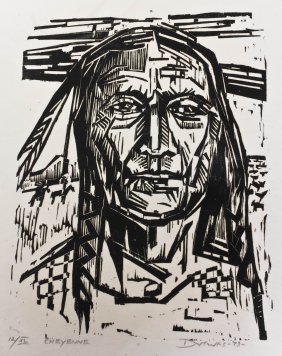

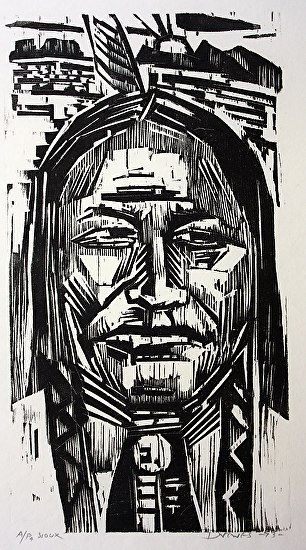

This year, the Morris Museum in Morristown has mounted a special exhibit of woodcut portraits of Native American people by the artist Werner Drewes (1899 - 1985) called “Celebrating Native American Heritage Month” – up through December 31, 2015.

I spoke with Assistant Curator Alexandra Willis about the story behind these seven woodblock prints, which are portraits of chiefs and other important members of the Blackfoot, Oto, Cree, Sauk, Cheyenne and Kickapoo tribes.

Jersey Arts: What do you hope visitors to the museum will take away from this exhibit?

Alexandra Willis: Not only a better understanding of how Native American Heritage Month came to be, but also a better understanding of the artist, Werner Drewes, and his many interests.

JA: Did Drewes have a strong interest in Native American culture?

AW: Even though Drewes visited New Mexico and California in the late 1920s, it wasn't until he taught printmaking and drawing at the Brooklyn Museum in the mid-1930s that his abstractions began having connections to Native American culture.

JA: Werner Drewes was better known as an American abstract artist than a portrait artist. How did this series of portraits come about?

AW: He actually had an extensive series of portraiture—mostly of friends and family—ranging from woodcuts to dry points and engravings. So, it really isn't uncommon for us to see portraiture from him.

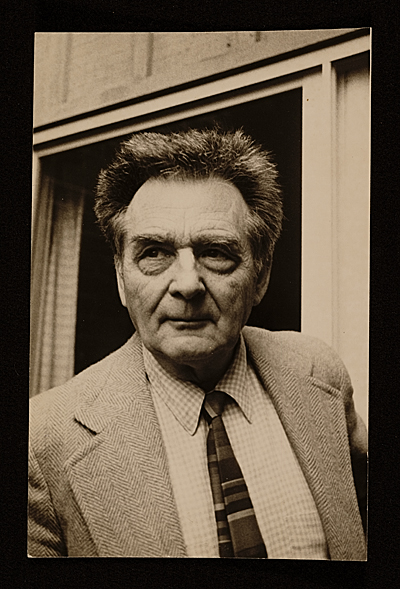

Drewes

JA: Could you give us some more background on Drewes? What should we know about him?

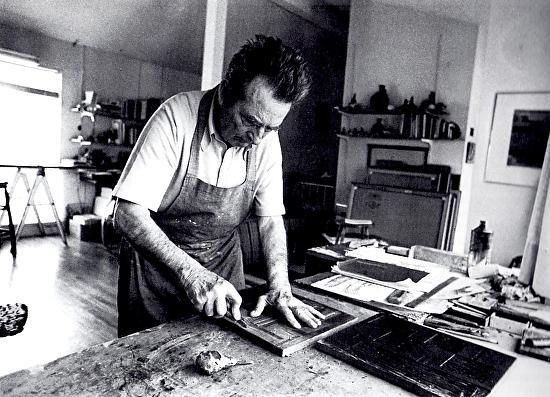

AW: Werner Drewes was a painter, printmaker and teacher, born in Canig, Germany in 1899. His father expected him to channel his artistic talents into a career as an architect, but Werner instead chose the vagabond life of an artist.

After being drafted into the army and serving his term on the front line in France during the first World War, Werner was admitted to the Bauhaus in 1921, where he studied under such artists as Klee, Itten and Muche.

Later, he traveled extensively throughout Italy and Spain to study such old masters as Tintoretto, Velasquez and El Greco. After marrying Margaret Schrobsdorf, a German nurse working in the Azores (Portugal), they traveled throughout South America, North America and Asia. Traveling was always an important source of inspiration for his work. In 1930, Werner immigrated to New York City with his wife and three young sons. Under Hitler, Germany had become too restrictive an environment for an abstract artist.

In New York City, despite the Depression, Werner joined other Bauhaus artists such as Mondrian and Feininger to make a living as an artist. This group became the core of the American Abstract Artists. Werner also taught at the Columbia University.

In 1946, he accepted a tenured position at Washington University in St. Louis. He remarried after his wife’s death in 1965, and moved to Point Pleasant in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to enjoy a rural retirement yet still be near the art hub of New York City. They then moved to Reston, Virginia where he continued his teaching, showing, creating and traveling into his 85th year.

To the very end, he cut his multiple plate color woodcuts, rubbed his prints by hand with a stylus, and added stylistic innovations.

JA: Let’s talk about a specific portrait from the exhibit – “Blackfoot”.

AW: The profile is very striking. The variation in line is extensive. Having studied printmaking in college, I know he only used one block of wood to carve into it, and only printed in one color, so he had to be very precise in his line placement and what he chose to carve.

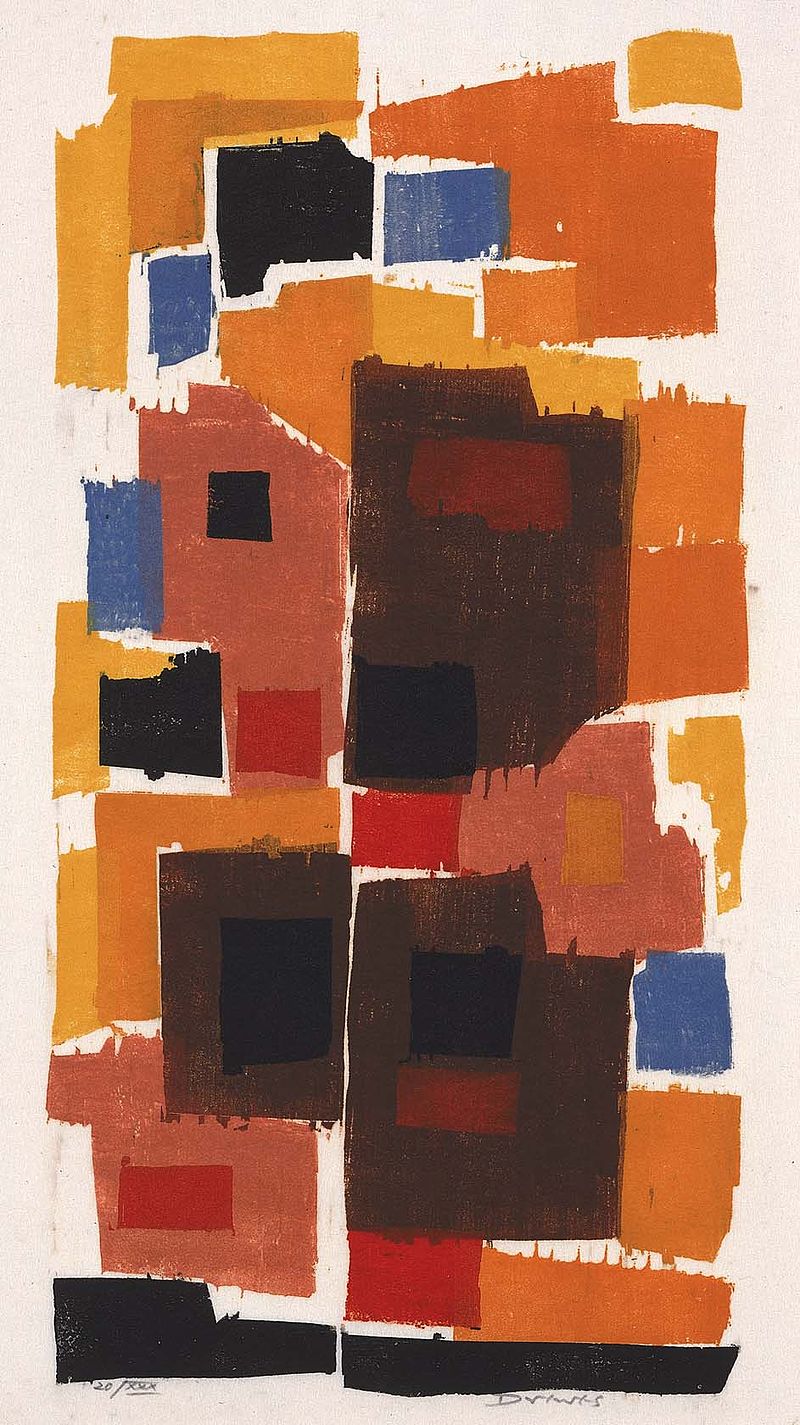

JA: Quite a contrast to his purely abstract works, like “Autumn Gold.” How do you explain the range and diversity of his work?

AW: Well, given that he studied with Bauhaus artists such as Paul Klee, Georg Muche and Johannes Itten, we can see how he was influenced by abstract art and color theory. However, we also see that Drewes was interested in learning from the old masters such as Tintoretto, Velasquez and El Greco while he traveled extensively throughout Italy and Spain.

It isn't unusual for artists to receive classical training prior to their own exploration. In Drewes’ case, he first studied the abstract and then moved on to the classical. These seven woodcut prints are actually very abstract.

JA: Why woodcuts? Why not drawings or paintings?

AW: Well, Werner Drewes was a printmaker. His body of art consisted primarily of different forms of printmaking – woodcut prints, linocuts, lithographs, etc. He hardly ever worked outside of the medium of printmaking in his lifetime. He produced approximately 700 fine prints in his lifetime and around 418 woodcuts.

JA: How did this special exhibit come together? How was it conceived and curated?

AW: It came together at the suggestion of Linda Moore, Executive Director of the Morris Museum, in honor of National Native American Heritage Month, and it was curated by me. It was really a matter of arranging them to keep the viewer’s attention—to keep the eye moving from piece to piece—which isn't hard given the variation of line and saturation of the ink.

JA: Why is it important to the Morris Museum to celebrate Native American Heritage Month in this way? Is this the first special exhibit at the museum that was designed to do that?

AW: It’s very important to the Morris Museum to acknowledge our nation’s cultural heritage, which began with the Native American Indians. This small exhibition compliments the Museum’s permanent Native American Gallery, which houses a wide variety of ethnographic materials representing numerous American Indian tribes throughout the United States. This is not the first special exhibit at the museum, nor will it be the last, so keep an eye on our website to see what’s next to come!